In 2018, it feels like we are living in a world divided

over so many issues. One of them being what can and

can’t be joked about and another being what is “right” and

“wrong.” This is why we wrote The Fugget. With people

so polarized on what’s going on in society, we thought satire

would do these issues more justice than “straight” news

coverage of issues ranging from censorship, to race and

gender relations, to society’s power balance.

Fortunately, the history of satire has shown that this

form of comedy thrives best in these unstable conditions.

From Nixon’s presidency fuelling National Lampoon’s

writing, to post-9/11 America giving The Colbert Report

endless material, to nearly every satire and comedy outlet

getting ideas spoon-fed to them through the actions of

President Donald Trump. Satire works best and is at its

highest importance when the world appears to be more of a

sitcom than it does real life.

Solutions wanted

Satire not only flourishes in these times because of how

easy the jokes can be to write, but also because people are

looking for an explanation to this madness; people want a

solution to these issues.

“Comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable,” said

Finley Peter Dunne.

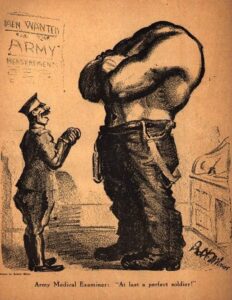

Dunne’s quote is vital to satire as it shows its importance

in educating and empowering “the people” to make

change and start conversations on issues within a society.

The quote also states the golden rule of satire – always

punch up. Punching up means to make fun of things people

can choose, not things they were born into or have (examples

include: race, disability, sexual orientation and disease).

This term also means to target people in power or

those making decisions on behalf of others.

Gift of satire

We’re extremely lucky to live in a country where questioning

and lampooning the actions of our superiors is a

protected right. Throughout history and even today, much

of the world would not even consider commenting on

taboo subjects such as inequality, religion or the actions of

their leaders. Citizens of countries like North Korea, Turkmenistan

and Russia don’t have the right to satirize nearly

anything. But that’s the beauty of satire. In a free nation,

the average person can poke fun at issues within their

world with nearly infinite possibilities.

Satire is not new and has been an important part of forwarding

discussion on political and social

issues since before Christ. Aristophanes,

considered the “King of Comedy” is often

regarded as one of the first satirists. The

writer believed gods, politicians and even

ordinary people could be made fun of – a

controversial viewpoint in ancient Athens.

His work can still be seen as it established a

trend in modern Greek theatre where writers

use updated versions of his plays to break

taboos. Aristophanes’ writing has also given

insight into the life and politics of ancient

Athens.

While Aristophanes’ work may be a

product of its time, most satire is. And like

his writing, satire can be as valuable as a

newspaper or a work of art in giving us a

look into what was going on in a society.

Satire can cover the political and social climate

and is a valuable piece of history. By

looking at the writing and seeing what came

after, you can often see a change of conversation

that the piece sparked.

When looking at the history of France’s

satire newspaper, Charlie Hebdo, one can

see a direct cause-and-effect of their work.

Most famously known for the 2015 shooting

that killed 12 and injured 11 of their staff,

historians will be able to look at this attack

and see the state of France at the time.

The attack was carried out in response to the paper’s

cover depicting The Prophet Muhammad – an extreme

taboo in some interpretations of Islam. The outlet had

pushed the limits of this topic three times before the shooting;

inciting responses ranging from attempted lawsuits, to

fire bombings on their office, to riot police having to guard

the paper’s offices.

France also has strict “Separation of the

Church and the State” laws which allow freedom

of speech for and against all religions, until

it falls under hate crime territory. Charlie Hebdo

states that these works are not an attack on Islam

and that France fought throughout its history to

have the freedom to question local powers like

the Catholic Church. “We have to carry on until

Islam has been rendered as banal as Catholicism,”

said Stéphane Charbonnier, Editor-in-Chief

of Hebdo.

After the attack, the following issue of the

paper ran 7.95 million copies in six languages,

compared to its typical print run of 60,000 in only

French. Whether you agree or disagree with what

the Charlie Hebdo printed, it demonstrates the

undeniable effect satire can have on a society. It

sparks conversation years later in a college newspaper

a world away.

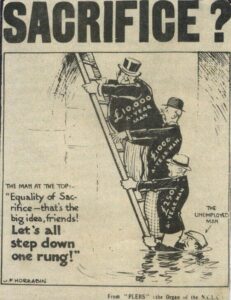

Satire doesn’t always have to be funny.

It just needs to ridicule and hold people

accountable, while aiming to inspire change

and improvement. Satire isn’t just about

making jokes out of nowhere, it’s about educating

people and creating conversations that

the news cannot. These aren’t just jokes for

the sake of jokes – satire can’t mock what

doesn’t exist.