I remember sitting in a psychiatrist’s office when I was seven. The fluorescent lights were bugging me. Not just because they strained my eyes–I could hear the buzzing when nobody else could. I was diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome, given a lollipop and sent home with a new understanding that I was special. When I told my classmates about it, I immediately regretted my decision. In the mind of immature elementary school kids, Asperger’s sounds like…something else much less medical and official. You’ve probably already heard what I mean, or see where this is going. Instead of feeling special, being called “ass burgers” made me hate my disability, thinking it was something wrong with me.

It was hard to change that mindset; I didn’t have any examples of autism as anything other than “the weird kid.” Growing up, I learned to appreciate my disability, but it wasn’t until my early 20s that I’d learn to not only accept, but love my autism. And part of that was some of the characters I’d see on screen that made me feel seen, like Abed from Community. Finding autistic characters became a hyperfixation, as did finding autistic creators.

There are more notable people like Neil deGrasse Tyson and Temple Grandin. But I later found out that others like comedian Dan Aykyrod, filmmaker Tim Burton and the creator of Pokemon, Satoshi Tajiri, all have autism. And this is just a drop in the bucket of successful autistic people. Daryll Hannah, Courtney Love, Eminem, Anthony Hopkins. All these people have autism of some kind. So my biggest question is this: Why is it so hard to find good autism representation in fiction?

One of the most notable autistic characters of the past decade is Shaun Murphy from The Good Doctor. Murphy is probably one of the worst depictions of autism I’ve ever seen. He’s a great surgeon, sure, but he’s a terrible doctor and a walking stereotype. For those who haven’t seen the show, Freddie Highmore plays Shaun Murphy, a surgeon with autism and Savant Syndrome.

While Murphy learns to interact with others throughout the series, it never sticks. There’s no real growth in his character. He keeps on making the same mistakes with little to no repercussions due to the episodic nature of the show. This all boiled down to the infamous “I AM A SURGEON!” scene that portrayed an unrealistic meltdown.

Beyond that, portraying his autism as a superpower (he sees his work in front of him) is also problematic. While Murphy also has savant syndrome, this disorder is often used in correlation with autism to treat it like a superpower. It leads into the “idiot savant” trope and establishes him more as a tool others can call in when needed, instead of a human being. In reality, only around one in ten people with autism have syndrome as well. So it frustrates me that the “idiot savant” is the most common form representation.

This concept of autism being a superpower dehumanizes us. Another infamous example is in The Predator (2018). Rory, the autistic child of the film’s leads, has an unnatural ability to understand languages. They actually call this “the next evolution of humanity” in the film. Or the film Rainman, where the titular character does math at a super human pace. I can’t speak for every other autistic person, but I’d like to see a more humanized representation.

Speaking of removing humanity, Sia made a film called Music. If you’ve seen it (or heard about it), you know why I’m bringing it up. For those who have no clue what I’m talking about, Music is a film about a recovering drug addict. She has to look after her autistic sister (the titular character) after their parent’s die. The film does some things right. Music uses, well, music to stop herself from getting overwhelmed in public (something I do). But a mass majority of what it did was very, very wrong. Firstly, they portray Music as a burden. To make it worse, they teach neurotypicals harmful means of dealing with autistic sensory overload. This includes forcing Music to the ground and holding her down until she stops having a meltdown.

You also see autism as a spectacle. There are a lot of reality shows that take one or more people with autism and treat them like something to be gawked at. The worst example of this is Love on the Spectrum, a show that follows autistic people finding love. While, on the surface, Love on the Spectrum looks like a show that celebrates autism, it only treats us like something to be watched. As I watched the first few episodes a while back I started noticing a pattern. The people dating neurotypicals were never successful. However, all the autistic couples were. While I don’t believe it was the showrunner’s intent, this comes off as them telling me to “stay in my lane,” or that I shouldn’t date non-autistic people. They should have tried harder to find success stories between autistic and neurotypical people. But instead, I have to spend every episode with Michael, whose misogyny is to blame instead of his autism. And they never try to help him get better, because he’s their ultimate spectacle.

All of these stereotypes exist, in part, due to the organization Autism Speaks. Contrary to the name and their claims, they are not an advocacy program. They used to support the “vaccines cause autism” study, they push for harmful behavioural therapy (ABA) and they have a long history of treating autism like a disease. The epitome of their discrimination came with the 2006 PSA “I am Autism.” This PSA treats autism like cancer, stating that it will ruin your life if your kid has it. According to them, autism will ruin your marriage, it’s silent “until it’s too late.” They even endorse shows like The Good Doctor and consulted on Music. It amuses and frustrates me that companies are choosing to pay Autism Speaks when they could spend less on an actually autistic consultant.

It’s not all bad, though. I want to spend the last half of this talking about good examples of autism representation.

If you’re a creator looking to write an autistic character, I’d suggest giving any of the following shows a watch. I had to reel these in because I could write an entire thousand word essay on why each is a great representation. A better example of a savant character like Murphy is Woo Young-Woo from Extraordinary Attorney Woo. Young-Woo has high functioning autism and lives on her own but isn’t estranged from her family. She has to set rules for herself on her first day of work. These include not repeating certain things, suppressing stims and not talking about her special interest, whales. In fact, while she has an amazing understanding of South Korean law, she often has to relate her work to whales in some way.

Now, all of this could seem problematic. But she ends up breaking all these rules fairly early on and has to have an adult conversation with her boss about discrimination after making a breakthrough in a case. This is all stuff I’ve had to do as an autistic person. While it doesn’t usually work out as well as it does for Young-Woo in real life, it’s nice to see these discussions being brought forward. The point ends up being that she didn’t make all these rules for herself to succeed. She just needed to be herself.

The primary difference between her and Murphy is how she handles her lack of social skills. She faces workplace discrimination and instead of throwing a tantrum, she fights harder. She also has friends who like her because of her differences. In The Good Doctor, Murphy has to convince other people to be his friends throughout the series. And even then, he’s treated as more of an acquaintance. But the first time we see Young-Woo in her adulthood, we see her eating lunch at her friend’s restaurant. The friend even comments on Young-Woo’s eating habits, as she needs food plated a specific way. This is better—it’s relatable to people who actually have autism. The Good Doctor is not.

I’ve also seen a lot of good autism representation in children’s media. While it’s important to have good representation in media aimed at adults, it’s even more important in media aimed at children. If you can convince a developing brain to accept these differences, it’ll lead to a brighter future.

Dreamworks has been particularly great at this in the last decade. For example, She-Ra and the Princesses of Power (a legitimately great show, by the way) reimagined every character from its 80s counterpart. It wasn’t just the designs either. While the rest of the princesses have magic, Entrapta gained power through tech. While she’s a villain in the source material, her eventual villainy comes from a misunderstanding in this show.

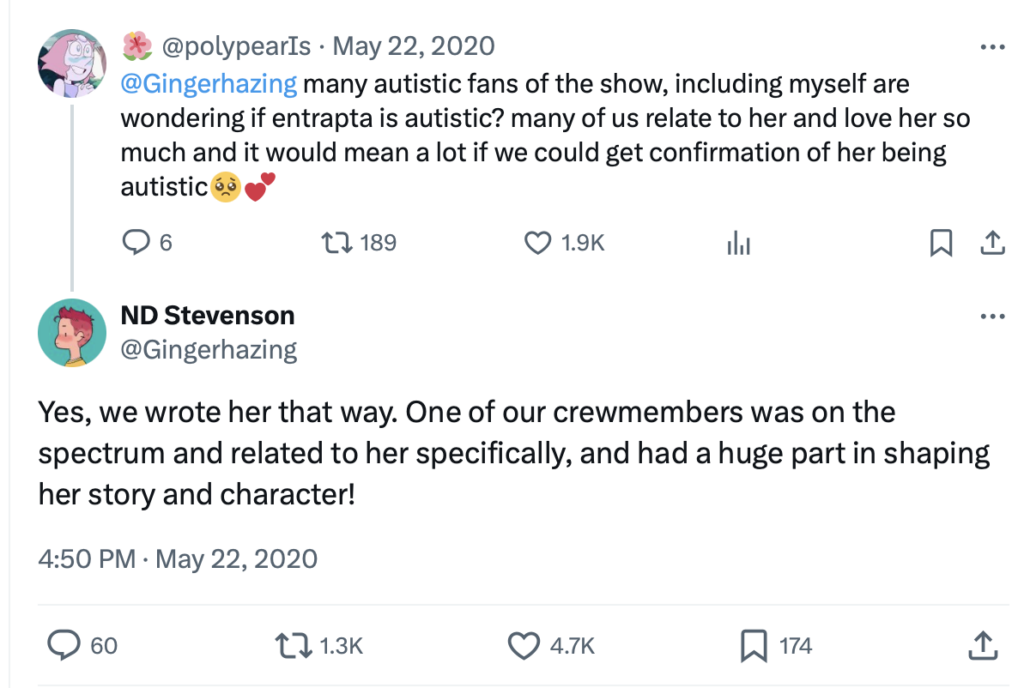

There’s also nothing wrong with writing an autistic villain, as long as their disability isn’t the reason for their villainy. While it’s never stated in the show she has autism, series creator N.D. Stevenson stated as much on X. And it makes sense. Entrapta has a hyperfixation with tech, struggles to communicate and won’t eat food unless it’s small.

In the end, autism has its fair share of good and bad representation, but it’s the bad that gets the most attention. I’ve noticed people both on and offline quoting the “I AM A SURGEON!” scene from The Good Doctor. And from my experience, that’s led to more and more people facing discrimination based on autism’s association with this type of representation.

I’ve had my fair share of people saying “but you’re so well spoken” or they start talking to me like I’m a kid. Autism isn’t a one size fits all sort of thing; we’re just as diverse in our views and abilities as those without it. The media we consume influences how we view the world, so I’d like to see some change in how people like me are portrayed.